Na Gaeil san Áit Ró-Fhuar

1845-1900: Tionchar an Ghorta ar Cheanada

“Níl file ná fáidh dár ghnáthaigh cumann na Naoi,

Níl ollamh ná bard le fáil a bhlas an sruth sí,

Níl duine den dáil gan cháin gan donas gan díth,

Faoi chogadh lucht Béarla a sháraigh orainn le dlí.”

- Aodh Mac Domhnaill (1)

In ainneoin na ndúshlán a bhí ann mar gheall ar ghorta, comhshamhlú agus brú polaitíochta, rinneadh iarrachtaí an Ghaeilge a chaomhnú agus a athbheochan i gCeanada. Bhí constaicí suntasacha agus dearcthaí sochaíocha le sárú ag na hiarrachtaí seo, áfach, a chuir le meath na teangan.

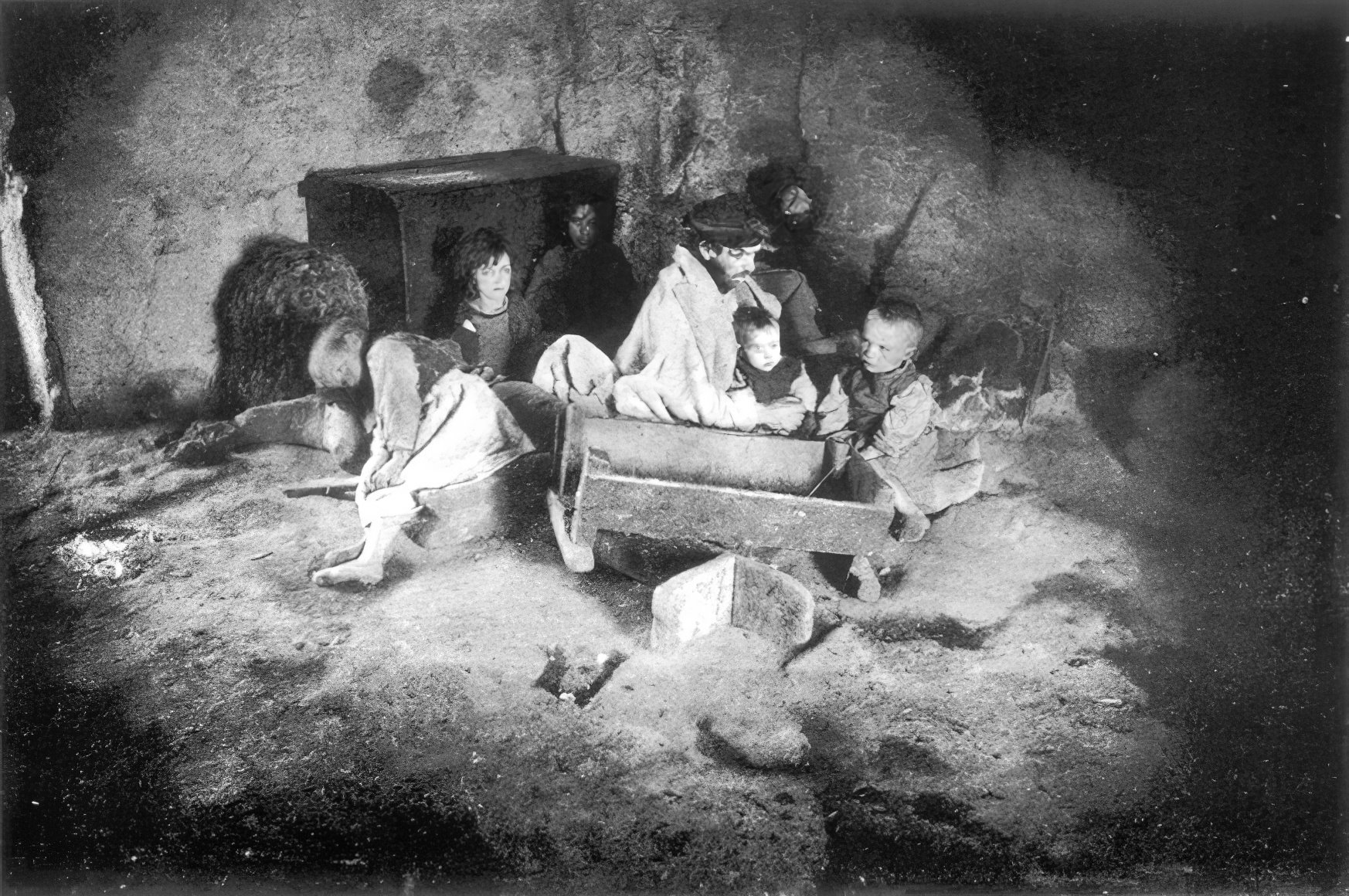

Sa bhliain 1845, thárla tréimhse cinniúnach d’Éirinn agus dá teanga nuair a bhuail an Gorta Mór. Mar gheall gur theip ar an bpríomhbhia stáplacha, thárla bás agus eisimirce go forleathan. Fé smacht na Breataine, bhí Gaeilgeoirí imeallaithe agus de shíor i mbéal an bháis de dheascaibh an ocrais, agus iad ag brath ar mhonashaothrú prátaí.(2) Mar thoradh ar chailliúint an phríomhbharr glasraí stáplacha seo, bhí géarchéim dhaonnúil ann, le galair forleitheadach, líon mór corpáin gan adhlacadh, agus fiú canablacht.(3)

Tionchar an Ghorta agus Eisimirce

Is ar na daoine is boichte in Éirinn, agus Gaeilge ag a bhformhór, is measa a bhuail an Gorta Mór. Ag deireadh an Ghorta, bhí timpeall 1.8 milliún duine tar éis teitheadh ó Éirinn, 1.2 milliún acu siúd nár labhair ach Gaeilge amháin.(4) Sheol siad go Ceanada ar longa cónra contúirteacha, mar níor ceadaíodh longa a bhí galar-inmhíolaithe dugaireacht i gcalafoirt na Stát Aontaithe. Bhí deacrachtaí ollmhóra ann an rabharta a láimhseáil ag stáisiúin coraintín Cheanada, cosúil le Oileán na nGael (Grosse Île). Tháinig na mílte Éireannaigh sa tréimhse1846-1847, agus thóg sé a lán laethanta chun iad a chur i dtír, agus mar sin bhí na paisinéirí a bhí ag fáil bháis le hocras, na heasláin agus na mairbh gafa i dteannta a chéile.(5) I measc an 100,000 Éireannach a dhein iarracht Québec a bhaint amach i 1847 amháin, fuair timpeall 25,000 dóibh siúd bás. Bhí an turas thar a bheith deacair agus tragóideach.

“Many died of sea-sickness on the voyage, and they were thrown overboard. The bones of these poor people whiten today all the way from Ireland to America in the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean… The graves of thousands of people who lived in this district during the Famine years are to be found on the banks of the Saint John River in New Brunswick, and on the banks of Lake Ontario and Erie. There are to be found the final resting places of many of Ireland's sons and daughters, an unbroken chain of graves where repose fathers and mothers, sisters and brothers in one commingled heap without a tear bedewing the soil or a stone to mark the spot.”(7)

Tionchar ar Cheanada

Bhí tionchar as cuimse ag na hÉireannaigh a tháinig slán ón dturas ar dhaonra beag Cheanada. In áiteanna mar Naomh Eoin, Bronsuic Úr (Saint John, New Brunswick), agus Torontó, Ontáirio (Toronto, Ontario), tháinig méadú beagnach fé dhó ar an ndaonra.(8) Bhí go leor leanaí ina n-aonar nuair a tháinig siad isteach go calafoirt cosúil le Montréal. Chaill siad a dtuismitheoirí agus a ndeartháireacha go tragóideach le linn an turais chrua go Ceanada. Tógadh isteach iad le teaghlaigh áitiúla agus uchtaíodh iad, grásta na trócaire i measc a leithéid de achrann, agus a d’fhág lorg domhain ar an bpobal go brách.

Ní raibh ach Gaeilge ag go leor Éireannach, agus thosnaigh an Ghaeilge ag éirí níos forleithne i gCeanada le linn an ama seo.(9) Fén mbliain 1867, le linn Cónaidhm Cheanada, bhí líon cainteoirí Gaeilge (na hÉireann agus na hAlban le chéile) ar an tríú grúpa teanga Eorpach is mó i gCeanada, tar éis Béarla agus Fraincis. Chomh maith leis sin, ba as Éirinn seachtar Aithreacha an Chónaidhm, ar a laghad, nó bhí tuismitheoirí Éireannacha acu.

Fé dhaonáireamh 1871, d’admhaigh ceathrú cuid de dhaonra Cheanada (846,000) gur de shliocht Éireannach iad. I mbeagnach gach mórbhaile agus cathair Cheanada, bhí daonra na nÉireannach níos flúirsí ná daonra na Sasanach ná na nAlbanach. Bhí na hÉireannaigh chomh ceannasach sin gur cheistigh an staraí Julian Gwyn an bhféadfaí iad a rangú mar ‘ghrúpa eitneach’ ar bith.(10) Cé nár thosnaigh bailiú na sonraí ar úsáid na teangan go dtí 1901, is deimhnitheach gur raibh an Ghaeilge ag méid suntasach den daonra, mar gheall ar na sluaite a bhí tar éis plódú isteach ag teitheadh ón ngorta. Ba Ghaeil gan ach an Ghaeilge mar theanga iad dhá thrian d’íospartaigh an Ghorta Mhór a bhí tar éis teacht chun na tire.

Meath agus Cur Fé Chois an Teangan

Tar éis an Ghorta, tháinig an meath is mó ar an nGaeilge. Ceanglaíodh an Ghaeilge le bochtanas, tráma, agus bás níos doimhne i meon an phobail, óir b’iad na cainteoirí Gaeilge an dream ba mhó a d'fhulaing ón nGorta Mór agus freisin toisc an bochtanais chrua a bhí rompu i gCeanada.(11) Measadh gur bealach marthanais agus ratha a bhí sa Bhéarla dos na leanaí. Breathnaíodh ar an nGaeilge mar theanga a bhain leis an aimsir caite agus le náire.(12)

Fiú amháin laistigh den phobal Gaelach, ba chúis trua iad na Gaeilgeoirí aonteangacha agus deineadh magadh fúthu.(13) Ghearr córas oideachais na Breataine pionós ar gach mionteanga laistigh den Impireacht. Riaradh pionóis chorpartha as teanga dhúchais an duine a labhairt, agus d'fhág sé na scolairi le mothúcháin náire fé chuid speisialta dá bhféiniúlacht agus freisin gur chéim ar gcúl agus mícheart go bunúsach é an Ghaeilge a úsáid.(14) Dhein cuid daoine iarracht a mbunús meabhlach Gaelach a cheilt trí ghlacadh le ainmneacha bréige de bhunadh Angla-Shacsanaigh.(15)

Spreag Ruathair na bhFíníní sna 1860idí agus sna 1870idí tuilleadh cur síos ar na hÉireannaigh chomh maith le feallmharú Tomás D’Arcy Mac Aoidh (Thomas D'Arcy McGee) ag Fíníní amhrasta i 1868, an chéad fheallmharú polaitiúil i stair Cheanada.(16) Bhí a lán den phobal Gaelach dátheangach i mBéarla nó i bhFraincis, agus measadh gur chúis náire é labhairt na Gaeilge.(17) Fé dheireadh na 1800idí, ní raibh ach céatadán beag leanaí fós á dtógáint leis an nGaeilge.

Iarrachtaí Athbheochana

In ainneoin na ndúshlán a bhain leis an nGorta Mór, leis an gcomhshamhlú agus leis an mbrú polaitiúil, rinneadh iarrachtaí an Ghaeilge a chaomhnú agus a athbheochan i gCeanada. Cuireadh ranganna Gaeilge poiblí ar fáil in Torontó chomh luath le 1862.(18) Tháinig cumainn Ghaelacha éagsúla chun cinn i gcathracha Cheanada le linn na tréimhse seo. Ba é an Celtic Society of Montréal a d'eagraigh staidéar ar theangacha agus ar litríocht na gCeilteach,(19) agus ba i mBaile Sheáin (St. John’s) a bunaíodh Society for the Preservation of the Irish Language. Bhí an Ghaeilge á múineadh fiú i scoileanna, ar nós St. Bonaventure’s i dTalamh an Éisc (Newfoundland).(20) Ach bhí constaicí suntasacha agus deachrachtaí sochaíocha ag baint leis na hiarrachtaí seo, áfach, a chur le meath na teangan.

Bille Teanga

Sa bhliain 1890, cuireadh tús le díospóireachtaí parlaiminte ar bhille cinniúnach an tSeanadóra Cheanada, Tòmas Raibeart Mac Aonghais, chun stádas oifigiúil a chur ar fáil do Ghaeilge na hAlban i gCeanada ar son na hÉireannach agus na nAlbanach araon.(21) In ainneoin litreacha tacaíochta a fháil ó gach cearn den tír, theip ar an mbille le vóta 49-6, mar gheall ar smaointearacht coilíneach seanaimseartha fé neamhthábhacht na mionteangacha. Léirigh sé seo na deacrachtaí a bhí ag pobail mhionlaithe aitheantas agus glacadh a fháil i gCeanada. Ó 1840-1900, bhí fáilte curtha ag Ceanada amháin roimh thart ar 600,000 Éireannach. Agus fós féin agus an 19ú haois ag druidim chun deiridh, bhí an cuma ar an scéal go raibh an Ghaeilge ag dul in éag ar fud an domhain.

(Image: McInnes, Thomas, Robert Dr., M.P. for New Westminister, British Columbia. Adapted from: Library and Archives Canada/Topley Studio fonds/PA-028316)

Le haghaidh lua, bain úsáid as: Ó Dubhghaill, Dónall. 2024. “1845-1900: Tionchar an Ghorta ar Cheanada.” Na Gaeil san Áit Ró-Fhuar. Gaeltacht an Oileáin Úir: www.gaeilge.ca

Is tuairimí an údair amháin iad aon tuairimí a nochtar, agus b’fhéidir nach léiríonn siad tuairimí Chumann na Gaeltachta.

-

Image citation: Left: Ireland and America by Henry Doyle, in Cusack, Mary Francis. An Illustrated History of Ireland from the Earliest Period. London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1868.

Right: Horrors of the emigrant ship - scene in the hold of the “James Foster, Jun.” digitally repaired from: Library of Congress/Harper’s weekly, 1869 March 27, p. 204/ Illus. in AP2.H32 Case Y.

Interior of a cabin in Carraroe, Co. Galway. Adapted from: National Library of Ireland via RTÉ.

Battle of Ridgeway, Adapted from: C.W. Library of Congress/Prints and Photographs Division/Popular Graphic Arts Collection/LC-DIG-pga-03244.

McInnes, Thomas, Robert Dr., M.P. (New Westminster, B.C.) Nov. 5, 1840 – 1904. Adapted from: Library and Archives Canada/Topley Studio fonds/PA-028316.

Mac Domhnaill, Aodh . 1850. Milleadh na bPrátaí. Ó Gráda, Cormac. 1994. An Drochshaol: Béaloideas agus Amhráin. Baile Átha Cliath: Coiscéim.

While the Famine was a natural disaster which had little effect in the rest of Europe, as former Irish President Mary Robinston states: “...in Ireland it took place in a political, economic and social framework that was oppressive and unjust.” Robinson, Mary. 1996. “President Mary Robinson at Grosse Ile, Quebec, August, 1994.” The Green Dragon. No.1.

All this came under a British government whose own head of famine relief held genocidal and racist anti-Irish sentiments, writing in 1846 that the Famine was a “...mechanism for reducing surplus population...The judgement of God sent the calamity to teach the Irish a lesson, that calamity must not be too much mitigated.” O’Riordan, Tomás. 2012. “Charles Edward Trevelyan.”Emancipation, Famine & Religion: Ireland under the Union, 1815–1870. Coláiste na hOllscoile Corcaigh, Online.

The population of Ireland would not rebound to pre-Famine levels until 2022.

Outfitted for 100 patients at a time, in 1846 alone Grosse Île catered to more than 32,000 emigrants and by May of 1847, 13,000 quarantined patients were docked in forty ships stretching in a line two miles down the Saint Lawrence River.

Even those who survived often faced disease, a were stereotyped as unclean. Canada’s first immigration law, just after the Famine, set to restrict any “undesirable pauper immigrants” such as the Irish from entering, due to the idea of the Irish as disease-spreaders. (Fraiman, Michael. 2019. Send them back’ nation. Maclean’s: September Issue.)

“The Schools’ Collection, Volume 0734, Page 462” by Dúchas © National Folklore Collection, UCD is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

This was not limited to city centres. Many Irish found their way to small, rural settlements. With no money to buy good land, and little civic authority to stop them, they squatted on unceded or unclaimed territories. In 1896 it was remarked that over half of the population of the living in the western Laurentians of Quebec, settlements such as St. Columban, were Irish. Stock, Sandra. 2023. “The Irish Heritage of the Laurentians.” Laurentian Heritage Web Magazine.

Most Irish speakers were illiterate in Irish, and could leave no trace in the record. One such example is the poet Ó Coileáin: “Do mhair file darbh ainm Ó Coileáin i mBóchuinne Carraig Airt 90 bl. ó shoin [1847]. Do chum sé dánta 's duanaireachta. Bhí teaghlach an ghéar-intinneach léannta aige agus gach dán a chum an t-athair choinnigh siad é go ndeachaidh siad uilig go Canada.” (A poet named Ó Coileáin lived in Bóchuinne Carraig Airt 90 yrs. ago [1847]. He composed songs and poems. This sharp-minded man had a very learned household and every verse that the father composed they kept until they all went to Canada.) T. Mc Ginley, Ros Goill, Co. Dhún na nGall. “The Schools’ Collection, Volume 1080, Page 297” by Dúchas © National Folklore Collection, UCD is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Gwyn, Julian. “The Irish in Napanee.” The Untold Story: The Irish in Canada. Ed. Robert O’Driscoll and Ed. Lorna Reynolds. Toronto: Celtic Arts of Canada, 1988. 355.

Historian Allen Levine notes that “There was no Irish ghetto in Toronto, yet it existed in the hearts and minds of the Irish nonetheless, often perpetuated by the community’s newspapers,” for example the Toronto Globe, which claimed in 1858 that the Irish were “as ignorant and vicious as they are poor. They are lazy, improvident and unthankful; they fill our poor houses and our prisons, and are as brutish in their superstitions as Hindus.” Levine, Allan. 2014. Toronto: Biography of a City. Douglas & McIntyre: Toronto.

“Imagine your reaction when your new masters tell you that the “barbarous dialect of your fathers”, through which you communicate with neighbours and friends, the “harsh-sounding primitive cant” (as they call your Irish language, Gaelic) that forms, delineates and defines our universe, was nothing but an inferior instrument of human communication, a product of the brains of lower forms of human development? ‘Your primitive Gaelic addles and muddles your brain,’ they tell you repeatedly. ‘Your insistence on perpetuating such a barbarian cant is the main obstacle to your achieving the plenitude of the human condition, both individually and socially. Such obtuseness condemns your children, and their children, to poverty, hunger, superstition and ignorance. Shame on you! But, luckily, salvation from such an ignoble fate, as even your priests (having been brought to heel) now insist, is well within your reach. On condition that you simply give up, abandon, your primitive native dialect, in all its guttural awfulness, and set yourself to mastering our extraordinarily sophisticated language of Beowulf, Shakespeare, Cromwell, Cambridge scholars, Westminster: our magical gateway to your raising yourself up to our higher level of civilization! Our esteemed Spenser got it right! Abandon your native Gaelic, in all its guttural awfulness, and thus elevate your standing among your fellows and your human worth in our estimation!’” Mac Síomóin, Tomás. 2020. The Gael Becomes Irish. Independently Published: Dublin. 30-31.

Aralt Mac Giolla Channaigh states: “Perhaps, as in Ireland, the famine had finally succeeded, where overt coercion had failed, to instill a sense of shame and inadequacy in Irish culture and language.” Mac Giolla Chainnigh, Aralt. 2005. The Irish Language in Kingston Ontario.

Many Irish avoided these schools altogether until the British Education Acts of 1870-1890, which instituted compulsory education for children up to the age of ten, converting children from their native culture to instead “think, speak, and be English.” These are recognized as some of the most damaging pieces of legislation for the Gaelic languages and Welsh and are part of the global system of repression occurring across the British Empire. Within twenty years of compulsory English-only schooling, severe language recession was noted in all the Celtic areas of the British Isles. In Canada, this left a population with no advanced knowledge of their own language, as Tomás Ua Néill Ruiseal noted in 1883: “Labhraíonn na seandaoine Gaeilge maith go leor, ach dá dtiocfadh Oisín nó Fionn ar ais chun beatha, níorbh fhéidir leo thuiscint na ndaoine óg, agus gan amhras níorbh fhéidir leis na daoine óga á dtuiscint ar aon chor. Ní thuigeann Gaeil na Ceanada ach na focail is simplí dá dteangan, mar is urus a mheas nuair nach bhfuil aon fhoghlaim acu inti.” (Ua Néill Ruiseul, Tomás. 1883. “Stáid na Gaedhilge agus Teangthadh Eile ins na Stáidibh Aontuighte (agus ‘san g-Canada).” Irisleabhar na Gaedhilge. 1.4.

This occurred in the authors own family in the 1860s, with the O’Sullivans (Ó Súileabháin) enmasse becoming the Selmans between just two censuses, to hide their Gaelic origin and ‘become English’. The Reverend Professor George Bryce alluded to this in 1887, writing from Canada’s Northwest that: “...Celtic origin is masked by their bearing Norse and Saxon names.” Bryce, George. 1887. “The Celt in the North-West.” Transactions of the Celtic Society of Montreal. Montreal: W. Drysdale & Co.

The Protestant ascendancy grew fearful that the French and Gaelic Irish, both mostly Catholic, might align and destabilize their grip on power. “An Irish priest is not and cannot be loyal to our Queen, our empire, or our people. He has no part or lot with us; he has no interest in us; he is an alien, though born within the bounds; and his oath of fealty is the kiss of Judas.” Kingsley, Charles. 1877. Charles Kingsley: his letters and memories of his life. 4th ed. 2. London: Henry S. King & Co.

The Satirist ‘Mac’ described the low value placed on the language by many of the incoming Irish in 1880: “When a man or woman steps on board the vessel which is to bear him or her away from Ireland, he or she leaves all knowledge of the grand old language behind...When asked if they speak Irish the answer invariably is, “No, it was not spoken in the town I came from, but it was spoken in the town adjoining ours.” I believe there are a few honourable exceptions who are proud to know the language… but whenever they speak it they are laughed at and ridiculed by those of their countrymen who expended the last vestige they possessed of it. Mackintosh, J. 1858. The Origin of the North American Indians. New York: Cornish, Lamport & Co.

Knight, Matthew Thomas. 2021. “"Our Gaelic Department": The Irish-Language Column in the New York Irish-American, 1857-1896”. Dissertation. Harvard University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. The Toronto Mirror reads “The Irish Class —This class, owing to the difficulty of procuring the proper elementary books, has only been able to listen to readings from the Irish Testament, and other books containing some of the beauties of the Irish language. At first, it was supposed that the primers could have been procured in New York. But it has been found necessary to go further, and Mr. Donahoe of Boston has sent to Dublin for them. Meanwhile, that enterprising publisher has forwarded to Toronto a beautiful copy of Moore’s Melodies in the Irish language, translated by the noble Archbishop of Tuam, from which readings will be given on Friday evening next, the 6th inst, at Mr. Keena’s Hotel, Colborne-street, at 8 o’clock in the evening. Other important business will also require a full attendance of the class.”

Along with public displays of the ancient Gaelic sports of iománaíocht (hurling) and péil (Gaelic football) Ryan, Dennis, and Kevin Wamsley. 2004. “A Grand Game of Hurling & Football: Sport and Irish Nationalism in Old Toronto.” The Canadian Journal of Irish Studies, vol. 30, no. 1.

Their appeal to the Canadians was: “Más ionúin leat na bráithre, bí leo go sásta socair” (If your kinsmen are beloved by you, be with them happily and steadily”

Fr. Michael A. Fitzgerald was president of St. Bonaventure’s school from 1883-1888: “When Father Fitzgerald became a member of the society for the preservation of the Irish language he started a class in Gaelic, which for a time was as popular as the violin and in the mastery of which pupils made about equal progress. There was a translation of Homer’s Iliad into Irish which some of the students were supposed to be able to appreciate.” Foster, F.G. 1979 Irish in Avalon: A study of the Gaelic language in eastern newfoundland. Newfoundland quarterly 74.4.

This was hoped to support Canada’s Irish and Scottish Gaelic speakers in the same way the recent French language bill had done for that language. McInnes stated: “at the lowest estimation we have at least one-quarter of a million of people who speak the Gaelic as their everyday language...there are as many as 200,000-250,000 Celts who speak the Irish language in their families and transact most of their business in their mother tongue...consequently, if this Bill becomes law, as I have no doubt it will, I do not see why it cannot serve every purpose for the Irish as well as the Scotch.” Government of Canada. 1890. “An Act to provide for the use of the Gaelic Language in Official Proceedings.” Debates of the Senate of the Dominion of Canada 1890. Comp. Holland Brothers. 4th session, 6th parliament. Ottawa: Brown Chamberlain.

All other cited references, numbers, or quotations as from: Ó Dubhghaill, Dónall (Doyle, Danny). 2019. Míle Míle i gCéin: The Irish Language in Canada. 2nd Ed. Boralis Press: Ottawa.

A Ghaeilic Mhín Mhilis!

Cuid de dhán a cumadh i nGloucester Theas (Enniskerry) Ontáirio agus a bhailigh Tomás Ua Baíghell. Foilsíodh sa nuachtán ‘The Irish-American’ é in 1860 sa chló Gaelach agus trí litriú pearsanta Uí Bhaíghell.

Seaicéad Fíníneach

Gabhadh an seaicéad fíor-annamh seo, a chreidtear gurb é an t-aon éide Fhíníneach a tháinig slán, le linn ionradh 1870 ar Québec. Bhí sé mar aidhm ag Bráithreachas na bhFíníní i Meiriceá Ceanada a ghabháil agus í a choinneáil go dtí go n-aontódh an Bhreatain le neamhspleáchas na hÉireann. Tháinig méadú suntasach ar náisiúnachas Cheanada de bharr na n-ionradh. Le caoinchead ó ©Parks Canada / Iarsma XX.88.9.1.

Feadóg Stáin Clarke

Déanta as pláta stán le plocóid béil as adhmaid, dhein Robert Clarke olltáirgeadh na bhfeadóg seo den chéad uair i 1840. Ardaíodh go tapa í mar cheann des na huirlisí is mó a úsáidtear i gceol na hÉireann. Ba leis an gceoltóir traidisiúnta Parker Buck (1858-1946) as Kingston, Ontáirio an ceann seo.

Spotsolas na nÚdar

Tá eagráin Ghaeilge de bheathaisnéisí údair ag teacht go luath