Na Gaeil san Áit Ró-Fhuar

1845-1900: The Famine Impact on Canada

“Here, less than 100 miles west of Great Britain, the heart of a great empire, a tragedy of epic proportions began to unfold. Before its end, the tragedy would take approximately 1 million lives. It would chase more than 2 million people from their homeland. It would nearly erase a culture and language thousands of years old.”

- Joseph O'Neill (1)

Despite the challenges posed by famine, assimilation, and political pressures, efforts were made to preserve and revive the Irish language in Canada. These endeavors, however, faced significant obstacles and societal attitudes that contributed to the decline of the language.

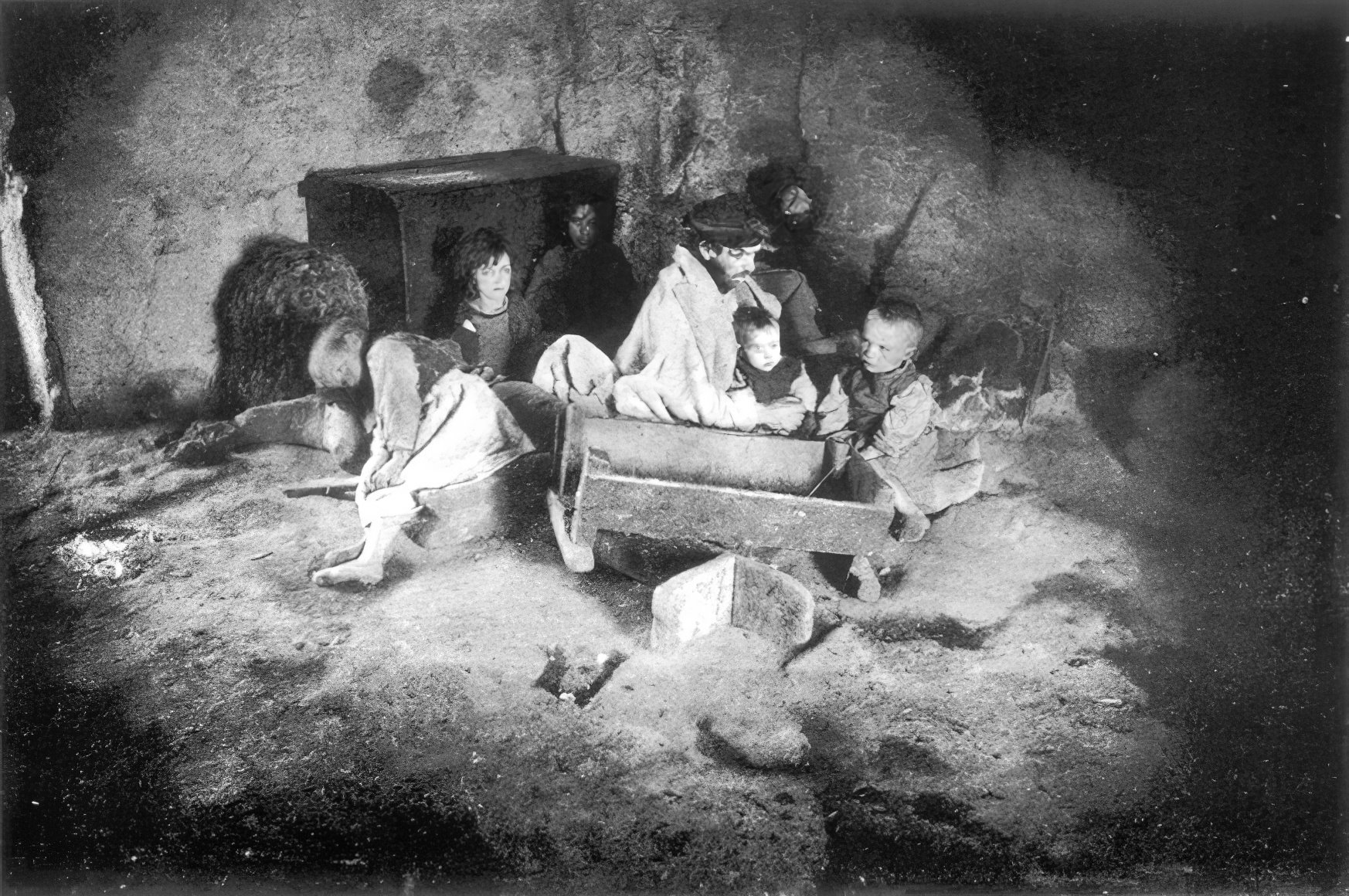

In 1845, a pivotal moment arrived for Ireland and its language when the Great Famine struck. The failure of a single food staple led to widespread death and emigration. Under British control, Irish-speakers were marginalized and perpetually on the edge of starvation, relying on a monoculture of potatoes.(2) The loss of this one staple crop resulted in a humanitarian disaster, with rampant diseases, mass unburied corpses, and even cannibalism.(3)

Famine's Impact and Emigration

The Famine hit hardest on Ireland's poorest people, most of whom spoke Irish. By the end of the Famine around 1.8 million people had fled Ireland, 1.2 million of those only speaking Irish.(4) They sailed to Canada on perilous coffin ships, as the United States didn't allow such disease-infested ships to dock. Canada's quarantine stations like Grosse Île (Oileán na nGael), struggled to handle the massive influx. Tens of thousands arrived in 1846-1847, and it took days to disembark, trapping starving passengers with the sick and dead.(5) Out of the 100,000 Irish attempting to reach Québec in 1847 alone, around 25,000 died.(6) The journey was incredibly difficult and tragic.

“Many died of sea-sickness on the voyage, and they were thrown overboard. The bones of these poor people whiten today all the way from Ireland to America in the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean… The graves of thousands of people who lived in this district during the Famine years are to be found on the banks of the Saint John River in New Brunswick, and on the banks of Lake Ontario and Erie. There are to be found the final resting places of many of Ireland's sons and daughters, an unbroken chain of graves where repose fathers and mothers, sisters and brothers in one commingled heap without a tear bedewing the soil or a stone to mark the spot.”(7)

Impact on Canada

The Irish who survived the journey had a profound impact on Canada's small population. In places like Saint John, New Brunswick, and Toronto, Ontario, their arrival nearly doubled the population.(8) Many children who arrived in ports such as Montréal were all alone. They had tragically lost their parents and siblings during the arduous journey to Canada. They were taken in and adopted by local families, which had a profound and lasting impact and was a generous act of compassion amid such adversity.

Many Irish spoke only Irish, which became more widespread in Canada during this time.(9) By 1867, during Canada's Confederation, the combined number of Irish and Scottish Gaelic speakers made them the third-largest European language group in Canada, following only English and French. In fact, at least seven Fathers of Confederation were from Ireland, or had Irish parents.

By the 1871 census, a quarter of the Canadian population (846,000) identified as ethnically Irish. In almost all major Canadian towns and cities, the Irish outnumbered both the English and Scottish populations. The Irish were so dominant that historian Julian Gwyn questioned if they could be classified as an 'ethnic group.'(10) While data on language usage only started being collected in 1901, it's certain that a significant portion of the population could speak Irish due to the influx of famine refugees, with two-thirds of Famine arrivals being Irish monolingual speakers.

Language Decline and Repression

After the Famine, the Irish language experienced its fastest decline. It became associated with poverty, trauma, and death, both because the Famine had disproportionately targeted Gaelic-speaking Irish and because of the harsh poverty they faced in Canada.(11) Survivors saw English as a means of survival and success for their children. Irish was seen as a language of the past and of shame.(12)

Even within the Irish community, monolingual Irish speakers were often pitied or looked down upon.(13) The British education system punished all minoritized languages within the Empire. Corporal punishments, solely for speaking one's own language, taught students to view an intrinsic part of themselves as humiliating, backwards, and inherently wrong.(14) Some Irish in Canada tried to assimilate by hiding their origins and adopting Anglicized names.(15)

The Fenian Raids of the 1860s and 1870s and the assassination of Thomas D’Arcy McGee by suspected Fenians in 1868, the first political assassination in Canadian history, fueled further demonization.(16) The mindset of viewing Irish as a conquered language took hold, leading to a decline in Irish speakers. The bilingual population often transitioned to English or French, and speaking Irish was seen as a source of shame.(17) By the late 1800s, only a small percentage of children were still being raised through Irish.

Efforts for Revival

Despite the challenges posed by the Famine, assimilation, and political pressures, efforts were made to preserve and revive the Irish language in Canada. Public Irish language classes were offered in Toronto as early as 1862.(18) Various Irish language societies sprang up in Canadian cities during this period. The Celtic Society of Montréal promoted the study of Celtic languages and literature,(19) while St. John's boasted the Society for the Preservation of the Irish Language. Even schools like St. Bonaventure's in Newfoundland taught Irish.(20) These endeavors, however, faced significant obstacles and societal attitudes that contributed to the decline of the language.

Language Bill

In 1890, parliamentary discussions opened on Canadian Senator Tòmas Raibeart Mac Aonghais’ landmark bill to provide official status for the Gaelic language in Canada.(21) Despite receiving letters of support from across the country, outdated colonial beliefs about the insignificance of minority languages led to the bill's failure, with a vote of 49-6. This reflected the difficulties faced by minoritized peoples in gaining recognition and acceptance in Canada. From 1840-1900, Canada alone had welcomed an estimated 600,000 Irish. And yet as the 19th century drew to a close, the Irish language seemed on the brink of extinction globally.

(Image: McInnes, Thomas, Robert Dr., M.P. for New Westminister, British Columbia. Adapted from: Library and Archives Canada/Topley Studio fonds/PA-028316)

For citation, please use: Ó Dubhghaill, Dónall. 2024. “1845-1900: The Famine Impact on Canada.” Na Gaeil san Áit Ró-Fhuar. Gaeltacht an Oileáin Úir: www.gaeilge.ca

Any views expressed are those of the author alone, and may not reflect the views of Cumann na Gaeltachta. Any intellectual property rights remain solely with the author.

-

Image citation: Left: Ireland and America by Henry Doyle, in Cusack, Mary Francis. An Illustrated History of Ireland from the Earliest Period. London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1868.

Right: Horrors of the emigrant ship - scene in the hold of the “James Foster, Jun.” digitally repaired from: Library of Congress/Harper’s weekly, 1869 March 27, p. 204/ Illus. in AP2.H32 Case Y.

Interior of a cabin in Carraroe, Co. Galway. Adapted from: National Library of Ireland via RTÉ.

Battle of Ridgeway, Adapted from: C.W. Library of Congress/Prints and Photographs Division/Popular Graphic Arts Collection/LC-DIG-pga-03244.

McInnes, Thomas, Robert Dr., M.P. (New Westminster, B.C.) Nov. 5, 1840 – 1904. Adapted from: Library and Archives Canada/Topley Studio fonds/PA-028316.

O’Neill, Joseph R. 2009. The Irish Potato Famine. Minnesota: ABDO Publishing.

While the Famine was a natural disaster which had little effect in the rest of Europe, as former Irish President Mary Robinston states: “...in Ireland it took place in a political, economic and social framework that was oppressive and unjust.” Robinson, Mary. 1996. “President Mary Robinson at Grosse Ile, Quebec, August, 1994.” The Green Dragon. No.1.

All this came under a British government whose own head of famine relief held genocidal and racist anti-Irish sentiments, writing in 1846 that the Famine was a “...mechanism for reducing surplus population...The judgement of God sent the calamity to teach the Irish a lesson, that calamity must not be too much mitigated.” O’Riordan, Tomás. 2012. “Charles Edward Trevelyan.”Emancipation, Famine & Religion: Ireland under the Union, 1815–1870. Coláiste na hOllscoile Corcaigh, Online.

The population of Ireland would not rebound to pre-Famine levels until 2022.

Outfitted for 100 patients at a time, in 1846 alone Grosse Île catered to more than 32,000 emigrants and by May of 1847, 13,000 quarantined patients were docked in forty ships stretching in a line two miles down the Saint Lawrence River.

Even those who survived often faced disease, a were stereotyped as unclean. Canada’s first immigration law, just after the Famine, set to restrict any “undesirable pauper immigrants” such as the Irish from entering, due to the idea of the Irish as disease-spreaders. (Fraiman, Michael. 2019. Send them back’ nation. Maclean’s: September Issue.)

“The Schools’ Collection, Volume 0734, Page 462” by Dúchas © National Folklore Collection, UCD is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

This was not limited to city centres. Many Irish found their way to small, rural settlements. With no money to buy good land, and little civic authority to stop them, they squatted on unceded or unclaimed territories. In 1896 it was remarked that over half of the population of the living in the western Laurentians of Quebec, settlements such as St. Columban, were Irish. Stock, Sandra. 2023. “The Irish Heritage of the Laurentians.” Laurentian Heritage Web Magazine.

Most Irish speakers were illiterate in Irish, and could leave no trace in the record. One such example is the poet Ó Coileáin: “Do mhair file darbh ainm Ó Coileáin i mBóchuinne Carraig Airt 90 bl. ó shoin [1847]. Do chum sé dánta 's duanaireachta. Bhí teaghlach an ghéar-intinneach léannta aige agus gach dán a chum an t-athair choinnigh siad é go ndeachaidh siad uilig go Canada.” (A poet named Ó Coileáin lived in Bóchuinne Carraig Airt 90 yrs. ago [1847]. He composed songs and poems. This sharp-minded man had a very learned household and every verse that the father composed they kept until they all went to Canada.) T. Mc Ginley, Ros Goill, Co. Dhún na nGall. “The Schools’ Collection, Volume 1080, Page 297” by Dúchas © National Folklore Collection, UCD is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Gwyn, Julian. “The Irish in Napanee.” The Untold Story: The Irish in Canada. Ed. Robert O’Driscoll and Ed. Lorna Reynolds. Toronto: Celtic Arts of Canada, 1988. 355.

Historian Allen Levine notes that “There was no Irish ghetto in Toronto, yet it existed in the hearts and minds of the Irish nonetheless, often perpetuated by the community’s newspapers,” for example the Toronto Globe, which claimed in 1858 that the Irish were “as ignorant and vicious as they are poor. They are lazy, improvident and unthankful; they fill our poor houses and our prisons, and are as brutish in their superstitions as Hindus.” Levine, Allan. 2014. Toronto: Biography of a City. Douglas & McIntyre: Toronto.

“Imagine your reaction when your new masters tell you that the “barbarous dialect of your fathers”, through which you communicate with neighbours and friends, the “harsh-sounding primitive cant” (as they call your Irish language, Gaelic) that forms, delineates and defines our universe, was nothing but an inferior instrument of human communication, a product of the brains of lower forms of human development? ‘Your primitive Gaelic addles and muddles your brain,’ they tell you repeatedly. ‘Your insistence on perpetuating such a barbarian cant is the main obstacle to your achieving the plenitude of the human condition, both individually and socially. Such obtuseness condemns your children, and their children, to poverty, hunger, superstition and ignorance. Shame on you! But, luckily, salvation from such an ignoble fate, as even your priests (having been brought to heel) now insist, is well within your reach. On condition that you simply give up, abandon, your primitive native dialect, in all its guttural awfulness, and set yourself to mastering our extraordinarily sophisticated language of Beowulf, Shakespeare, Cromwell, Cambridge scholars, Westminster: our magical gateway to your raising yourself up to our higher level of civilization! Our esteemed Spenser got it right! Abandon your native Gaelic, in all its guttural awfulness, and thus elevate your standing among your fellows and your human worth in our estimation!’” Mac Síomóin, Tomás. 2020. The Gael Becomes Irish. Independently Published: Dublin. 30-31.

Aralt Mac Giolla Channaigh states: “Perhaps, as in Ireland, the famine had finally succeeded, where overt coercion had failed, to instill a sense of shame and inadequacy in Irish culture and language.” Mac Giolla Chainnigh, Aralt. 2005. The Irish Language in Kingston Ontario. The Committee on Irish Language Attitudes Research found that an Irish speaker in 1975 was still commonly thought of as “…smaller, uglier, weaker, of poorer health, more old-fashioned, less educated, poorer, less confident, less interesting, less likeable, lower class, of lower leadership ability, lazier and more submissive compared to an English speaker. Basically, and Irish speaker is more undesirable.” Committee on Irish Language Attitudes Research. 1975. Report. Dublin Stationary Office: Dublin. 454.

Many Irish avoided these schools altogether until the British Education Acts of 1870-1890, which instituted compulsory education for children up to the age of ten, converting children from their native culture to instead “think, speak, and be English.” These are recognized as some of the most damaging pieces of legislation for the Gaelic languages and Welsh and are part of the global system of repression occurring across the British Empire. Within twenty years of compulsory English-only schooling, severe language recession was noted in all the Celtic areas of the British Isles. In Canada, this left a population with no advanced knowledge of their own language, as Tomás Ua Néill Ruiseal noted in 1883: “Labhraíonn na seandaoine Gaeilge maith go leor, ach dá dtiocfadh Oisín nó Fionn ar ais chun beatha, níorbh fhéidir leo thuiscint na ndaoine óg, agus gan amhras níorbh fhéidir leis na daoine óga á dtuiscint ar aon chor. Ní thuigeann Gaeil na Ceanada ach na focail is simplí dá dteangan, mar is urus a mheas nuair nach bhfuil aon fhoghlaim acu inti.” (Ua Néill Ruiseul, Tomás. 1883. “Stáid na Gaedhilge agus Teangthadh Eile ins na Stáidibh Aontuighte (agus ‘san g-Canada).” Irisleabhar na Gaedhilge. 1.4.

This occurred in the authors own family in the 1860s, with the O’Sullivans (Ó Súileabháin) enmasse becoming the Selmans between just two censuses, to hide their Gaelic origin and ‘become English’. The Reverend Professor George Bryce alluded to this in 1887, writing from Canada’s Northwest that: “...Celtic origin is masked by their bearing Norse and Saxon names.” Bryce, George. 1887. “The Celt in the North-West.” Transactions of the Celtic Society of Montreal. Montreal: W. Drysdale & Co.

The Protestant ascendancy grew fearful that the French and Gaelic Irish, both mostly Catholic, might align and destabilize their grip on power. “An Irish priest is not and cannot be loyal to our Queen, our empire, or our people. He has no part or lot with us; he has no interest in us; he is an alien, though born within the bounds; and his oath of fealty is the kiss of Judas.” Kingsley, Charles. 1877. Charles Kingsley: his letters and memories of his life. 4th ed. 2. London: Henry S. King & Co.

The Satirist ‘Mac’ described the low value placed on the language by many of the incoming Irish in 1880: “When a man or woman steps on board the vessel which is to bear him or her away from Ireland, he or she leaves all knowledge of the grand old language behind...When asked if they speak Irish the answer invariably is, “No, it was not spoken in the town I came from, but it was spoken in the town adjoining ours.” I believe there are a few honourable exceptions who are proud to know the language… but whenever they speak it they are laughed at and ridiculed by those of their countrymen who expended the last vestige they possessed of it. Mackintosh, J. 1858. The Origin of the North American Indians. New York: Cornish, Lamport & Co.

Knight, Matthew Thomas. 2021. “"Our Gaelic Department": The Irish-Language Column in the New York Irish-American, 1857-1896”. Dissertation. Harvard University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. The Toronto Mirror reads “The Irish Class —This class, owing to the difficulty of procuring the proper elementary books, has only been able to listen to readings from the Irish Testament, and other books containing some of the beauties of the Irish language. At first, it was supposed that the primers could have been procured in New York. But it has been found necessary to go further, and Mr. Donahoe of Boston has sent to Dublin for them. Meanwhile, that enterprising publisher has forwarded to Toronto a beautiful copy of Moore’s Melodies in the Irish language, translated by the noble Archbishop of Tuam, from which readings will be given on Friday evening next, the 6th inst, at Mr. Keena’s Hotel, Colborne-street, at 8 o’clock in the evening. Other important business will also require a full attendance of the class.”

Along with public displays of the ancient Gaelic sports of iománaíocht (hurling) and péil (Gaelic football) Ryan, Dennis, and Kevin Wamsley. 2004. “A Grand Game of Hurling & Football: Sport and Irish Nationalism in Old Toronto.” The Canadian Journal of Irish Studies, vol. 30, no. 1.

Their appeal to the Canadians was: “Más ionúin leat na bráithre, bí leo go sásta socair” (If your kinsmen are beloved by you, be with them happily and steadily”

Fr. Michael A. Fitzgerald was president of St. Bonaventure’s school from 1883-1888: “When Father Fitzgerald became a member of the society for the preservation of the Irish language he started a class in Gaelic, which for a time was as popular as the violin and in the mastery of which pupils made about equal progress. There was a translation of Homer’s Iliad into Irish which some of the students were supposed to be able to appreciate.” Foster, F.G. 1979 Irish in Avalon: A study of the Gaelic language in eastern newfoundland. Newfoundland quarterly 74.4.

This was hoped to support Canada’s Irish and Scottish Gaelic speakers in the same way the recent French language bill had done for that language. McInnes stated: “at the lowest estimation we have at least one-quarter of a million of people who speak the Gaelic as their everyday language...there are as many as 200,000-250,000 Celts who speak the Irish language in their families and transact most of their business in their mother tongue...consequently, if this Bill becomes law, as I have no doubt it will, I do not see why it cannot serve every purpose for the Irish as well as the Scotch.” Government of Canada. 1890. “An Act to provide for the use of the Gaelic Language in Official Proceedings.” Debates of the Senate of the Dominion of Canada 1890. Comp. Holland Brothers. 4th session, 6th parliament. Ottawa: Brown Chamberlain.

All other cited references, numbers, or quotations as from: Ó Dubhghaill, Dónall (Doyle, Danny). 2019. Míle Míle i gCéin: The Irish Language in Canada. 2nd Ed. Boralis Press: Ottawa.

A Ghaeilic Mhín Mhilis!

Part of a poem (Oh Smooth, Sweet Gaelic!) composed in South Gloucester (Enniskerry) Ontario and collected by Tomás Ua Baíghell. Published in ‘The Irish-American’ newspaper in 1860 using the Gaelic type and Ua Baíghell’s personal orthography.

Fenian Jacket

This exceptionally rare jacket, believed to be the only surviving Fenian uniform, was captured during the 1870 invasion of Québec. The American Fenian Brotherhood aimed to seize British Canada and hold it until Britain would agree to Ireland's independence. The invasions led to an significant increase in Canadian nationalism. Courtesy of ©Parks Canada / Object XX.88.9.1.

Clarke Tin Whistle

Made of tin-plate with a wooden mouth plug, these whistles were first mass-produced in 1840 by Robert Clarke. This model rapidly became one of the most used instruments in Irish music. Owned by traditional musician Parker Buck (1858-1946) of Kingston, Ontario